Understanding the Ostrich Effect:

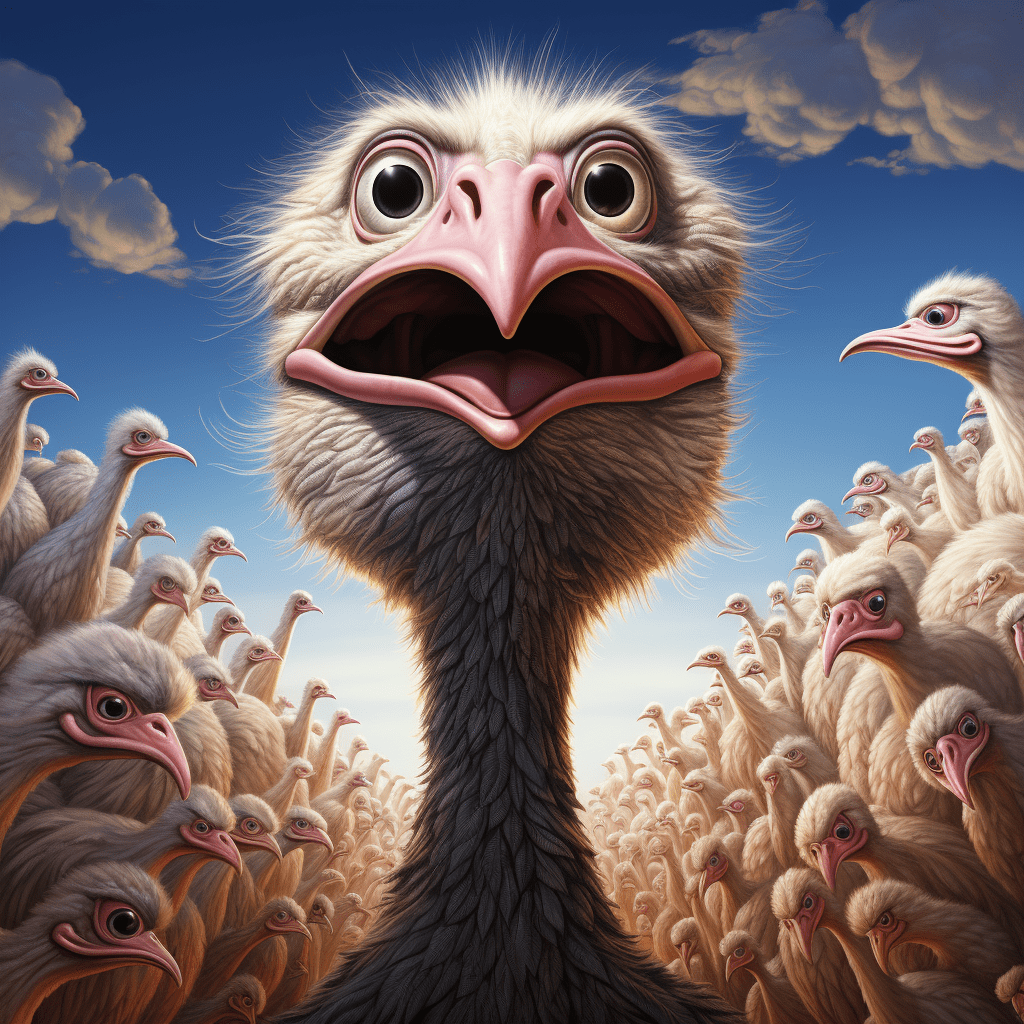

In the fascinating world of psychological phenomena within education, the Ostrich Effect takes centre stage today. This cognitive phenomenon, named after the often humorous image of ostriches burying their heads in the sand, profoundly influences how students approach learning challenges.

Defining the Ostrich Effect:

The Ostrich Effect, in an educational context, refers to a child’s tendency to avoid difficult subjects or evade uncomfortable learning situations. Much like the ostrich burying its head to escape perceived danger, students might avoid topics they find challenging or situations that make them uncomfortable. Imagine a child who constantly requests bathroom breaks right when a challenging math lesson begins. Or, picture another child who suddenly becomes disruptive whenever the class delves into a complex reading assignment. These are instances of the Ostrich Effect in action, where pupils try to escape demanding topics or situations that make them uneasy. Teachers may encounter this phenomenon more often than they realise in their primary classrooms (I have witnessed this kind of situations many times during my teaching career).

To truly grasp the Ostrich Effect, we need to look into the research that surrounds this cognitive phenomenon. Studies indicate that students often employ avoidance as a coping mechanism when they fear failure, embarrassment, or believe their abilities are limited. This behaviour frequently aligns with a fixed mindset, where students see their capabilities as static and unchangeable.

Research by Tali Sharot

In an innovative study led by Tali Sharot and her team, participants displayed tendencies aligned with the Ostrich Effect. The research, published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, revealed that individuals often choose to ignore information that challenges their pre-existing beliefs or opinions. Similarly, students may avoid subjects that challenge their self-perception of competence.

Practical Strategies for Educators:

- Foster a Safe and Inclusive Environment: Create a classroom atmosphere where making mistakes is celebrated as part of the learning process. Emphasise that errors are stepping stones to success and not something to be ashamed of.

I have used this in my practice, and I have learned that consistency in its use is key to success. Praise children’s mistakes when you know they’re trying their best, and only correct them if the mistake has been made due to not trying their best. - Cultivate a Growth Mindset: Building on the work of Carol Dweck, instill a growth mindset within your students. Teach them that abilities can be developed through effort and perseverance.

One way I’ve put this into action is by regularly sharing stories of well-known individuals who faced challenges and setbacks on their path to success (I also use characters from books we’ve just read, or famous people that children idolise (such as Lionel Messi). - Set Goals and Monitor Progress: Guide students in setting realistic and achievable goals. Break down larger tasks into smaller, manageable steps. Encourage regular reflection on their progress.

It is important that our lesson’s success criteria follow this guidance in order for children to know what little steps they need to complete to achieve the main goal. - Leverage Peer Support: Promote peer collaboration and support. Sometimes, students feel more comfortable seeking help from classmates. Group activities and study sessions can help break down barriers.

With my previous Year 3 class, this approach yielded remarkable results. The children supported each other, leading to an overall improvement in their progress. Another noteworthy advantage is that children often explain concepts differently from adults, which can greatly benefit their understanding, particularly when a concept hasn’t been fully grasped through adult explanations. - Encourage Positive Self-Talk: Assist students in recognising and altering negative self-talk. Encourage the use of positive affirmations like “I can” and “I will.”

I initially had reservations about this approach, but it has consistently proven me wrong. I encourage you to use this strategy even if you’re concerned it might initially alienate the children because it has a significant positive impact on their psychological well-being.

Practical Examples:

Let’s explore practical scenarios that illustrate the Ostrich Effect and how educators can tackle it:

Scenario 1: Avoiding Difficult Subjects

Challenge: A student consistently avoids participating in math class.

Solution: Introduce engaging and interactive math activities that make learning fun. Gradually, the student may become more willing to engage with the subject.

Scenario 2: Fear of Public Speaking

Challenge: A student dreads public speaking and avoids class presentations.

Solution: Begin with smaller, less intimidating presentations and gradually increase the complexity. Create a supportive environment where classmates provide constructive feedback.

Scenario 3: Reluctance to Seek Help

Challenge: A student struggles with a subject but hesitates to ask for assistance.

Solution: Offer one-on-one sessions or peer tutoring. Highlight that seeking help is a sign of strength and a proactive approach to overcoming challenges.

The Ostrich Effect serves as a reminder of the power of confronting fears and challenges head-on. As educators, it’s our duty to recognise and address this phenomenon in our classrooms. Cultivating a growth mindset, creating a supportive environment, and encouraging positive self-talk, can help empower our students to face difficulties with resilience and determination. Remember, it’s about lifting their heads high with confidence, not burying them in the sand.

Bibliography:

Sharot, T., Guitart-Masip, M., Korn, C. W., Chowdhury, R., & Dolan, R. J. (2012). How dopamine enhances an optimism bias in humans. Current Biology, 22(16), 1477-1481.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine Books.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302-314.

More interesting research in these blog posts:

Children’s Egocentrism: The Three Mountains Task

Understanding children’s egocentrism is essential for educators to maximize academic progress. The Three Mountains Task, a tool developed by Jean Piaget and Bärbel Inhelder, is instrumental in studying egocentrism. This task enables researchers to observe how children’s egocentric thinking shapes their perception of the world.

The Galatea Effect: Children’s Learning Through Belief and Potential

Learn about the incredible influence of the Galatea Effect, where students’ belief in their own abilities can shape their educational journey. Drawing on the study of psychologist Albert Bandura, this post explores the big impact of self-efficacy on students’ performance and outcomes.

High Expectations in the Classroom: The Pygmalion Effect

The Pygmalion Effect, is a study that revealed the impact of teacher expectations on student performance. Explore how high expectations in the classroom can ignite remarkable growth and potential in students, surpassing preconceived limitations. Learn practical strategies for teachers to cultivate a growth mindset, create a positive classroom culture, and…